Conditions: Disorders of the Sense of Smell (Olfaction)

Olfactory dysfunction refers to impairment of the sense of smell. It can be a highly distressing condition as the sense of smell plays a crucial role in our daily lives. Coping strategies such as seeking alternative ways to appreciate flavors, maintaining good hygiene practices, and being mindful of potential safety hazards can help individuals adapt to living with this condition. Alteration of smell may be in various forms:

Anosmia - inability to smell anything

Hyposmia - decreased ability to smell

Parosmia - distorted sense of smell

Phantosmia - perception of a smell not present

Hyperosmia - increased acuity of smell

Commonly misunderstood, flavor is the combination of smell and taste. Olfactory dysfunction is usually not coincidental with a taste disturbance.

Dangers of olfactory dysfunction

In addition to losing the pleasurable aspect of smell, olfactory dysfunction can pose some health risks. Examples of these are potentially injecting spoiled food, not detecting smoke, and not detecting the smell of a gas leak. One safety measure an affected individual may take is ensuring that plenty of smoke detectors are in the home and workplace and changing their batteries twice a year. Avoiding use of gas stoves or fireplaces, or at least taking extra efforts to ensure they are not left on may also prevent a disaster. Ideally, however, one’s sense of smell may be restored, which is possible in some circumstances.

How the olfactory system works

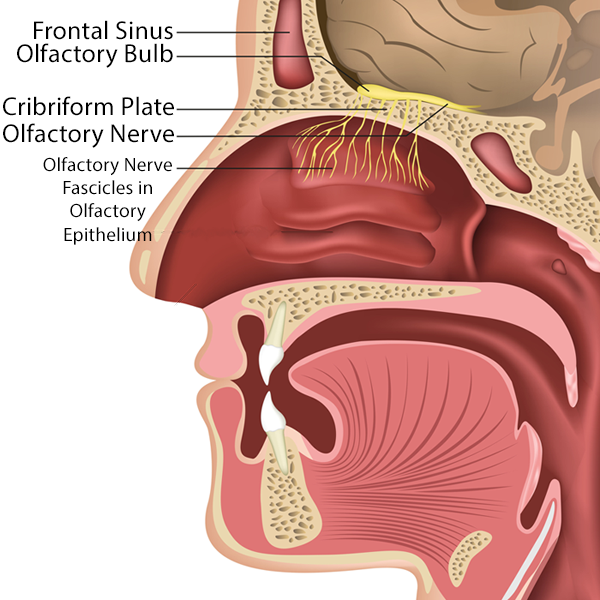

The olfactory system relays information on types of particles within the nose to the brain, yielding the psychologic experience of smell. The left and right olfactory nerves pass from the brainstem under the brain and along the skull base to a site above the nasal cavity. From there, small nerve branches pass through the many small passageways in the skull base (the cribriform plate) to enter the nasal cavity. These microscopic nerve fibers in the nose run through the thin lining covering bone, called the epithelium, and distribute only within a small area toward the top of the nasal vault.

Odorants, the particles that may be airborne and brought into contact with the olfactory epithelium due to nasal airflow, make contact with the nerve branches within the olfactory epithelium, triggering a series of molecular events that generate nerve signals to the brain conveying data in a pattern characteristic of a particular smell. The olfactory system's incredible sensitivity and ability to detect countless odors make it a remarkable gateway to our sensory experience.

The olfactory nerve branches passing down through the skull base into the nose cover a small area of olfactory epithelium capable of detecting odorants.

The olfactory bulbs are shown in green. The olfactory mucosa, where odorant particles are detected by olfactory nerve fibers, is shown in blue.

Causes of olfactory dysfunction

The causes of olfactory dysfunction can vary, including 1) decreased nasal airflow (specifically decreased airflow over the olfactory epithelium), 2) infections, 3) head injuries, 4) primarily neurologic conditions such as Parkinson's disease or Alzheimer's dementia, and 5) tumors.

If the pathway for airborne odorants to physically transit to the small patch of olfactory epithelium in the nose is blocked, their smell cannot be detected. Physical blockage of the air passage to the olfactory cleft may occur with swelling of the nasal lining (possibly from infection), nasal polyps (a specific condition of inflammation and swelling), scar tissue, tumor, and not breathing through the nose.

Infections, whether viral, bacterial, or fungal, can alter the olfactory nerve’s ability to transmit information to the brain, even when the odorant makes contact with the olfactory nerve fiber. An infection may damage the nerve, the nasal surface lining (mucosa) around the nerve fibers, the olfactory bulb, or brain structures or circuits. Restoration of olfaction may or may not occur after resolution of the infection. Nose and sinus infections commonly diminish olfaction.

Head injuries may injure the olfactory nerve directly.

Certain neurologic conditions have a high prevalence of olfactory dysfunction, such as in Parkinson’s disease (up to 100%), Alzheimer’s dementia (90%), and frontotemporal dementia (96%). The exact mechanism of how these conditions cause olfactory dysfunction is not completely understood.

A tumor of the nose/sinus or brain may compress or invade and destroy the olfactory nerve or brain structure/circuits. A tumor may also block access of air to the olfactory epithelium, which is described in #1 above.

Olfactory testing

Clinical testing of olfactory dysfunction typically consist of assessing a patient’s perception of an odorant. Perception may be gauged by one’s ability to detect the odor, identify the odor, discriminate one odor from another, remember an odor, or estimate the intensity of an odor. Various products exist for these purposes, including scratch and sniff odorized pads and specialized wants containing an odorant. A simple assessment sometimes used in the absence of such products is the presentation of a well-known odorant available in most offices (such as coffee grounds) to the patient for detection or identification.

This page